In May 2018 I seized an opportunity to ride the beautiful and dangerous Suhua Highway (蘇花公路) from Hualien City to Su'ao in Yilan. I had previously taken this same route on bicycle back in 2013—a harrowing trip I’ll never forget—so I was eager to drive a scooter and experience it at a different pace. I also visited a number of historic sites along the way, including several former Shinto shrines, as part of an ongoing project documenting various elements of the Japanese colonial legacy in Taiwan. Much of the highway itself also owes something to Japanese engineering, having opened to vehicular traffic in 1931, but it has been continuously repaired and expanded since then.

My first stop as I exited Hualien City was a Shinto shrine1 located next to the Port of Hualien at the north end of town. In the late 1930s an aluminum factory on this site to support the Japanese war effort. Sometime around 1941 a small, unranked shrine2 was constructed next to the main office. The factory was bombed by American forces but the shrine survived the war, presumably unscathed, although few records of the original shrine are known to exist. Apparently we don’t know what it originally looked like nor what kami (spirits) were venerated there.

The factory was acquired by the Taiwan Fertilizer Company sometime after the war and the shrine was destroyed, leaving only the concrete base seen in this blog published in 2011. Some sources I consulted suggest a storm might have ripped the shrine from its foundation but it is far more likely it was dismantled after the promulgation of a government edict requiring the removal of Japanese imperial relics in 19743.

Much to my surprise I found the shrine recently restored, part of a larger effort to transform the Taiwan Fertilizer Company’s newly-built deep ocean water extraction plant into a tourism factory4. The restoration project, completed in 2015, was informed by clues derived from what remained of the base, photos and records of similarly-sized shrines, and a general understanding of construction methods of the time, but the historical accuracy of such projects is often a matter of debate5. That being said, this replica serves as a useful model for identifying several features common to small Shinto shrines across Taiwan.

This reconstructed shrine features a torii (鳥居), the traditional arched gateway; chōzubachi (手水鉢), the stone and bamboo washbasin used for ritual ablution; a short sandō (参道), or visiting path; ema (絵馬), little wooden plaques ordinarily used to convey wishes to the enshrined kami, though this replica was never consecrated; and a honden (本殿) in the nagare-zukuri (流造) style, held in place by winch straps, presumably to prevent it from blowing away in a typhoon. A pair of stone lanterns visible in pictures of the opening ceremony were nowhere to be seen. Also missing are the customary pair of komainu (狛犬), or guardian lion-dogs, although I’m not sure such a small shrine would ordinarily feature any.

Heading north from Hualien I merged with Provincial Highway 9, formally embarking upon the Suhua Highway near Jǐngměi Station (景美車站), and made my way to the old street at the heart of the small town of Xincheng6, the gateway to Taroko National Park. Here I made a brief pitstop at the rustic Xincheng Film Studio (新城照相館), a century-old building featured in the film Eternal Summer 盛夏光年, but it wasn’t open. Next door is the Jiāxìng Fruit Ice Shop (佳興冰果室), famous for its lemonade. I picked up two bottles for the long ride ahead.

After a brief excursion to confirm the location of an old sentry post next to the railway line at the edge of town7 I crossed the Taroko Bridge (太魯閣大橋) into Xiulin and continued north to St. Bernard Catholic Church (聖伯納天主堂) in the village of Chóngdé (崇徳). The entrance to this church features two stone lanterns from the former Shinto shrine in this area8 and a crude orange torii made out of metal pipe.

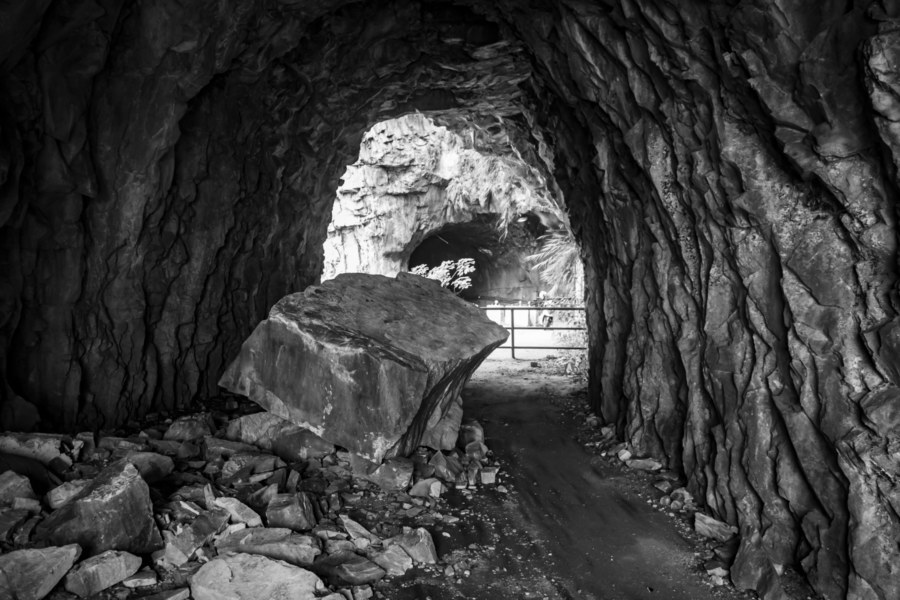

Immediately to the north of Chongde is one of Taiwan’s most majestic landscapes, Qīngshuǐ Cliff (清水斷崖)9. These beautiful gneiss and marble cliffs rise from the deep ocean to the Qingshui Mountain peak, 2,408 meters above sea level but only 2 kilometers from the shore. The old Suhua Highway ran along the edge of these cliffs, following the winding contours of the coastline, but many of the most precarious sections have been bypassed with tunnels built over the course of the last several decades. Some of the abandoned sections are accessible but most are not—and without any maintenance, parts of the old road have collapsed into the sea10.

Xiaoqingshui Lookout (小清水休憩區), located on the far side of that first tunnel while heading north, provides public access to a short section of the old highway, and many travellers stop here to get a better view of the cliffs. From here you can appreciate the immensity of the mountains rising from the deep ocean and the insignificance of the works of humankind. Both the highway and the railway line are impressive engineering achievements—but they are dwarfed by the scale of nature here on the very edge of the continent.

The Suhua Highway dates back to Japanese times but the railway line running along this far shore was not completed until 1979. Formally known as the North-Link Line (北迴線), it was one of the Ten Major Construction Projects (十大建設) promulgated by Chiang Ching-kuo. Prior to the opening of the North-Link the railway network terminated at Su’ao Station (蘇澳車站); the railway lines of eastern Taiwan, which date back to the 1910s, were totally isolated from the rest of the country until this link was established.

What was meant to be a leisurely trip up the Suhua Highway with ample time for detours became somewhat more constrained by a change in the weather. Not long after leaving Xincheng the forecast worsened, and the chance of rain edged closer to certainty as I continued north. I had no interest in driving in a storm so I ended up taking fewer discretionary stops than originally intended, which is just as well, for progress was not as swift as planned.

Construction work was visible all along the highway, part of an ongoing improvement project that began in 2011. This project was partly in response to a deadly landslide in 2010 that claimed 26 lives. Several of the most landslide-prone sections of coastal road are being replaced by tunnels, nearly 25 kilometers in all. Other areas are being reinforced, ideally to prevent the collapse of sheer rock faces and the like. Although this may sound worrisome, the Suhua Highway is far safer than it was decades ago, when it rightfully earned a reputation as one of the world’s most dangerous roads.

For most of its history the Suhua Highway had long sections that could only handle one-way traffic. Into the 1980s there were six control stations along the highway to control the flow of traffic in each direction. Motorists had to queue and wait for others to pass before proceeding to the next stop. This can be seen in archival footage, starting with this video shot in the 1930s, not long after the opening of what was then known as the Seaside Highway (臨海道路). This video (only on Facebook) shows highway conditions in 1973 from a coach bus, the most common way to get to and from eastern Taiwan in those days. This system was only abolished in 1990 after the completion of another major road improvement project.

One of the first landmarks you’re likely to see after crossing into Yilan is the Guanyin Stone (觀音石), named after a waterfall located near this bend in the highway. This boulder tumbled down the mountainside and landed here in 1993, only meters from a bridge that surely would have been destroyed on impact. It has since been converted into a small shrine to Guanyin, popularly known as the goddess of mercy. Many motorists stop here to pay their respects—but this lonely stretch of highway, 18 kilometers in all, will become obsolete as soon as the new Guanyin Tunnel (觀音隧道) enters into service in 2019.

Soon I came down from the winding mountain roads and found myself on the edge of Wǔtǎ Village (武塔村), a settlement populated by the Atayal people, the third-most populous of Taiwan’s Indigenous peoples11. Here I stopped to examine a roadside monument, Sayon’s Bell (莎韻之鐘), a modest bell tower gated by another torii. At that time I wasn’t sure what it was all about—but having done some research into it, there’s quite a story to tell.

Flashback to 1938, not long after the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War, when a Japanese schoolteacher working in Wuta received a notice drafting him into the military. In those days the village was located approximately 20 kilometers deeper into the mountains12 and could only be reached on foot so some schoolchildren volunteered to help their teacher carry his luggage into town. A typhoon struck while the party was coming down from the mountains and a 17 year-old Atayal girl, Sayun Hayun, was knocked off a bridge by surging stormwaters, never to be seen again.

Sayun’s tragic death merited only a brief report in the newspaper—but the story was soon spun into one of patriotic devotion, of a young Indigenous woman who gave her life to ensure victory on the frontlines. Seizō Kobayashi, the governor-general of Taiwan, awarded her home village with a bronze bell, honouring them for their sacrifice, and many more articles were written, inspiring a popular song and eventually a feature-length black-and-white film released in 1943. (If you’re curious, the entire movie is currently available on YouTube!)

None of this was accidental, of course. Japanization accelerated in 1937 with the advent of the Kōminka movement (皇民化運動), a set of policies intended to further assimilate Taiwanese, and there was obviously an interest in showing rapid progress since the disastrous Musha Incident (霧社事件) of 1930, in which more than 600 Indigenous people were killed in a brutal crackdown. The colonial authorities recognized the propaganda value of Sayun’s story, intentionally crafted a persuasive narrative, and produced media to influence the population.

The original bell and accompanying monument were destroyed sometime after the arrival of the KMT but the story was not forgotten. Following the democratization movement of the 1990s the bell was recast and the municipal government built the present structures, the bell tower and a torii, at what is officially known as Sayun Memorial Park (莎韻紀念公園) in 1998. What motivated people to recreate an artifact of imperial wartime propaganda in this place? You could write an entire thesis exploring this question so I won’t provide any trite answers here; it’s a topic deserving of further thought and consideration.

My next stop was the former Nán’ào Shrine (南澳神社), originally built in the mid-1930s and located just a little north and west of the station on a south-facing hillside. Not much remains of this shrine apart from an overgrown stairway; I could not locate a pedestal, stone lanterns, or anything else of interest. Obviously the original shrine was renovated, probably in the 1970s, and replaced with something—but nothing remains to provide any clues13.

Not long after passing the small town of Dōng’ào (東澳)14 I stopped at a roadside temple venerating construction workers and engineers who died while building the Suhua Highway. Formally known as Qìng’ān Hall (慶安堂), and less formally as Kāilù Xiānfēngyé Temple (開路先鋒爺廟, roughly: “Road-Building Pioneers Temple”), it was constructed in 1997 to house the Sōnan-hi (遭難碑, “Accident Monument”), a stone memorial dating back to 1917. This stone originally featured two names but the list has grown to 13, several of them Japanese, making it one of a very small number of Taiwanese temples where Japanese people are worshipped15. This list is by no means complete; many other monuments to victims of accidents and disasters can be found all along the length of the highway, but this one is the oldest16.

With daylight running out and storm-clouds lingering over the mountains to the west I was glad to reach the Nánfāng’ào Lookout (南方澳觀景臺), the last major stop on the highway before coming down into Su’ao proper. Nanfang’ao remains one of Taiwan’s most important fishing ports, and it’s one I’ve previously covered on this blog—just have a peek at this full post for more. But the day was not quite over, and I made good use of my remaining time.

Beyond the lookout I finally left the Suhua Highway by taking an overgrown access road to the top of Pàotáishān (砲台山, literally “Fortress Hill”), which occupies a strategic position overlooking Su’ao Harbour. Its name is derived from a Qing dynasty fortification originally constructed here in 1884, during the Keelung Campaign of the Sino-French War, and expanded in 1889. Nowadays there is a small park on top of the hill with a recreation of the original fort, which was destroyed long ago, and a pair of cannons, provenance unknown.

Immediately before arriving at the hilltop park I paused to investigate an old bunker by the roadside. Emblazoned with the white sun, a KMT emblem, it probably dates to the post-war period, although I haven’t been able to find any credible information to back this up, nor was able to find a match for the characters above the entrance (chénkàn gùshǒu 沉看固守, something along the lines of “watch quietly and defend strongly”). Much to my surprise, the bunker was occupied! After entering with a flashlight I saw a man sitting in the darkness, completely still and obviously afraid. Without making eye contact I retreated, shouting apologies in English and Chinese, and drove off. I figured he’s probably a runaway fisherman, fleeing the abuse and exploitation endemic to Taiwan’s notoriously inhumane fishing industry. I wouldn’t date mention this were it not nearly a year since I was there—surely he’s moved on since then.

Fortress Hill is also home to the ruins of the Su’ao Kotohira Shrine (蘇澳金刀比羅神社), named after Kotohira-gū (金刀比羅), a famous shrine in Shikoku, Japan, widely revered for protecting seafarers and fishermen17. This is one of only a handful of Kotohira shrines built in Taiwan18, possibly because they were privately-funded rather than state-sponsored. As you might expect, the shrine was oriented toward the sea, and the top of the visiting path affords a fantastic view of the harbour.

The former entrance to the shrine was destroyed to facilitate the widening of the Suhua Highway, which snakes around the base of the hill, so the stone stairway is only accessible from the top. Clamber down a level and you’ll find some stone lanterns and a monument obscured by the overgrowth. This monument is a dedication stone with a surprisingly legible inscription—usually these are defaced—reading: established on April 20th in the second year of the Shōwa period, 1927 (昭和二年四月二十日鎮座). The pedestal that once supported the honden can be found in the park, but it now features a monument to the Su’ao chapter of the Lions Club. Further down the access road leading down the hillside is Tiānjūn Temple (天君廟), reputedly the location of the original Qing dynasty military encampment, and several more stone pedestals taken from the Kotohira shrine19.

Before leaving town I captured a photo of the derelict Su’ao Railway Turntable (蘇澳扇形轉台), a relic of when Su’ao was the last stop on the line20. I’ve already covered the function of such turntables at length in my full post about the Changhua Roundhouse 彰化扇形車庫, so browse on over there if you’re curious about how it operated. Such turntables were necessary in the age of steam but no longer serve much of a purpose. From the look of it you might expect there to have been another fan-shaped garage at this location but I’ve seen no evidence of this, and US military maps of the area show nothing more than a railroad yard as of 1945.

With only a little light to spare, and having miraculously evaded the rain, I headed north through Lányáng Tunnel (蘭陽隧道) to have a quick look at Yuèmíng New Village (岳明新村), one of approximately 35 settlements of refugees from the Dachen Islands (大陳群島). These islands, now part of China, were evacuated by the KMT in 1955, a story detailed in this brief post. As with most other Dachen villages I’ve visited this one was quite rundown and nearly empty. I continued on to the far shore north of Su’ao Harbour and snapped the final DSLR photo of the day, having put 100 kilometers of road behind me.

There was one last surprise in store for me on this ride. While heading west out of Yueming New Village into the outskirts of a small Hakka village named Gǎngkǒu (港口, in English we’d have called this place “Portsmouth”) I noticed something interesting by the roadside. It was a small stone slab shrine, the kind where you’d ordinarily expect to find a land god, so I was taken aback at the sight of a red-faced figure wielding a comical knife in the gloomy interior.

Stopping to take a closer look, I realized this was one of the Five Cardinal Armies (五營神將), a tradition introduced in this post about an extraordinary temple in Lukang. In this case, what you see here is the Southern Army (南營兵將), which I confirmed by visiting the temple at the heart of the nearby village. The five armies are distributed all around the village, ostensibly to protect it from danger. I’ve visited dozens of these little shrines all around Taiwan but nowhere else have I seen straw soldiers like these21; most feature war flags.

My ride ended in Luodong, where I snapped up an inexpensive hotel room and finally got some rest. I was hoping to continue over the mountains to Taipei the following day but ended up getting rained out, so this is the extent of my field notes from this particular trip. As usual, I picked up numerous leads while conducting research for this post, so I’ve plenty more to see should I find time to return to the Suhua Highway.

- This shrine is typically described in Chinese as the Japanese Aluminum Company’s Port of Hualien Factory Shinto Shrine (日本鋁株式會社花蓮港工場構內社). ↩

- Shinto shrines in Taiwan were organized into several groups according to a Meiji-era system of classification adapted for local use: official shrines (kansha 官社), which were imperial (kanpeisha 官幣社) or national (kokuheisha 國幣社) and assigned one of three ranks; assorted or civic shrines (shosha 諸社 or minsha 民社), which were ranked at the level of prefecture (fusha 府社), county (kensha 縣社/県社), and savage land (hansha 藩社)—with the previous three at the same level—town (gōsha 鄉社), and village (sonsha 村社); and finally the unranked shrines (mukakusha, 無格社 or 社祠). ↩

- This edict issued by the Ministry of the Interior in 1974 is formally known as Main Points on the Elimination of Taiwan Japanese Era Colonial Rule Memorials and Historical Remains Manifesting Japanese Imperialism’s Sense of Superiority (清除日據時代表現日本帝國主義優越感之殖民統治紀念遺跡要點). Among other points it demanded the complete destruction of all Shinto shrines, although it allowed for the repurposing of common temple accoutrements like stone lanterns, as long as they were sufficiently modified so as to no longer appear Japanese. For context, this edict followed the Japan–China Joint Communiqué in 1972, which normalized relations between the two nations, further isolating the Republic of China on Taiwan. In other words, sour grapes is what led to the wholesale destruction of an incredible amount of Taiwan’s colonial history in the late 1970s. The full text of the edict is available in Chinese on this blog. ↩

- Tourism factories are common in Taiwan; many companies open small museums, showrooms, and themed restaurants to host families and tour groups. If you’re curious about the rest of what you’ll find at this particular tourism factory, try this post. ↩

- Yoshihisa Amae provides an accessible introduction to this debate in Pro-colonial or Postcolonial? Appropriation of Japanese Colonial Heritage in Present-day Taiwan, Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 2011. ↩

- Xincheng is also home to an interesting Shinto shrine, now the Xincheng Catholic Church (新城天主堂), but I didn’t stop there on this particular trip. Hopefully I’ll get around to posting about it some other time. ↩

- There are dozens of abandoned military installations along the east coast, usually on one side or another of major river crossings. None of them are particularly photogenic or overly interesting. ↩

- Chongde was formerly known as Déqílí (德其黎), and its shrine was known as 德其黎祠. What remains of the shrine is located behind what is now the Xiulin No. 6 Public Cemetery (秀林第六公墓). Previously my research indicated there was nothing to see but more recently I learned there’s enough to warrant a return trip and a closer look. ↩

- Tourist brochures describe the Qingshui Cliffs as a 21 kilometer-long stretch of coastline with an average height of 800 meters but it’s only about 10 kilometers from Chongde to Hérén Station (和仁車站) and the road itself is probably cut at around 150 meters elevation. ↩

- Unfortunately I wasn’t able to visit some of the more impressive sections of broken coastal highway on this ride. The most intriguing parts are also the most dangerous and the government has done a reasonably good job making these places difficult to access. ↩

- Another curious trace of Japanese colonization is Yilan Creole Japanese, a mixture of Japanese and Atayal spoken by around 3,000 people in several villages near Wuta. ↩

- This pattern of Indigenous resettlement has been repeated hundreds of times all around Taiwan. The Japanese approach to colonizing the mountainous interior initially involved cutting footpaths and stationing police officers in Indigenous villages. Uncooperative Indigenous groups were forcibly relocated to lowland areas to enhance the ability of the colonial authorities to monitor activity and suppress dissent. Under KMT rule many more villages were forcibly resettled in the lowlands, especially in the early 1950s, and sometimes in the same settlement as former enemies. I was intrigued to learn that Old Wuta (舊武塔 or 老武塔) is still accessible to the determined hiker. Not much remains, but if you’re curious to see the gateposts of the school, they’re visible in this post. ↩

- A Japanese post made in 2009 reveals a bronze bust of Chiang Kai-shek occupying the space at the top of the stairs. Perhaps that bust is now enshrined in the Garden of the Generals in Daxi. ↩

- Apparently the former Dong’ao Shrine (東澳祠) was one of the oldest in the area, dating back to 1920, but nobody seems to have located any of its relics. Sources I consulted indicate it was located around the Presbyterian Church next to Shéshān (蛇山), pretty much where you’d expect to find it. ↩

- This Chinese Wikipedia entry lists ten temples venerating Japanese people in Taiwan. There are likely to be a few more since I notice one missing: the Mazu Temple in Ximending, which is home to a small shrine to Kōbō-Daishi. ↩

- Older monuments related to the highway can be found but they don’t memorialize accidents. The most significant of these is the Luó Dàchūn Road-Building Monument (羅大春開路紀念碑) in Nan’ao, which commemorates the efforts of Luo Dachun (羅大春), a Qing general, to build a footpath along this rugged shoreline in 1875, part of an island-wide attempt to shore up defences after the Mudan Incident (牡丹社事件) in 1874. From what I’ve read it was seldom used by anyone except soldiers due to poor conditions and the threat of attack by Indigenous people defending their land. ↩

- There is a fascinating history to this god, which can be traced back to a deified crocodile in Hindu lore. In the Meiji era the government enacted a policy separating Shinto and Buddhist shrines, obscuring the syncretic origins of customs that were later exported to Taiwan. It is also worth mentioning that Kotohira is roughly analogous to Mazu, the most widely venerated deity in modern-day Taiwan, which might help explain why there were never more than a few shrines of this type. ↩

- Kotohira shrines were typically located next to major ports; Keelung and Kaohsiung both had one. There are two more slightly inland, one in Hemei, Changhua, and the other on the old sugar factory grounds in Dalin, Chiayi. Not much remains of any of the others from what I can tell—but I’ve only visited the shrine in Keelung, which was upgraded in the 1930s, losing its original association with Kotohira. ↩

- This section was informed by many great posts about the history of Paotaishan; for more information in Chinese try here, here, here, here, and here. ↩

- Technically Su’ao Station is still the end of the line since the railway branches off at Sū’àoxīn Station (蘇澳新站), the previous station. By what logic is it “Su’aoxin” and not “Xinsu’ao”? ↩

- This tradition might be unique to the Wúwěi Harbour (無尾港) area—run a search for 稻草兵將 and this little corner of Yilan is the only place that comes up. ↩

Write a Comment